The Niagara region includes the Niagara Escarpment AVA and the “Lake Plain” area north of the escarpment. The AVA derives its name from the Niagara Escarpment, a limestone ridge that runs for over 650 miles through the Great Lakes Region and the proximity of this ridge to the lake results in a moderate climate.

The Niagara Escarpment is important to winegrowing in both western New York and in the Niagara region of Ontario Canada. The AVA is essentially a continuation of Ontario’s Niagara Escarpment region on the western side of the Niagara River. The New York portion of the Niagara Escarpment has a continental climate that is heavily influenced by both Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Winters are cold, preventing the overwintering of some insect species harmful to grapes. The moderating effects of the lakes extend the growing season, and its northern latitude makes for very long sunny days in the summer months.

Geology

The Niagara Escarpment is a massive topographic feature, about 650 mile long, that formed from sediments deposited in a shallow warm sea between 445-420 million years ago. Over millennia, the coral reefs transformed to a hard dolomite (dolostone of limestone).

The formation can be traced in a giant horseshoe from near Rochester, through the Niagara Peninsula south of Lake Ontario to Hamilton, and north to Tobermory on the Bruce Peninsula. It then disappears beneath the water of Lake Huron to reappear on Manitoulin Island, across northern Michigan and down the west side of Lake Michigan to the state of Wisconsin. The final shape of the escarpment, the Niagara River and Great Lakes were formed 12,000 years ago on the retreat of the Ice Age glaciers. The Niagara Escarpment slopes to the north dropping 200’ towards Lake Ontario. The AVA’s vineyards are planted between 200-400’ of elevation on these soils that were once lake shore and lake bed.

The deep gravelly limestone- and clay loam-based soils in the Niagara Escarpment AVA have proven ideal for viticulture. The limestone content puts the soil in the correct range for optimal nutrient uptake and the clay soil components hold moisture for the long summers.

Climate

The lakes are the region’s largest temperature moderator and extend the growing season in conjunction with the escarpment by keeping air moving during times that are risky for frost. This has made the escarpment a prime fruit growing region for hundreds of years. The proximity of the escarpment to the lakes also results in decreased cloud cover, especially in the summers, which enjoy more sunshine than most of the northeastern regions.

Western New York is known for its lake effect snows, which can result in highly localized, sometimes intense and even historic snow events. However, snow accumulation actually protects vines from deep freeze temperatures.

Lake effect storms across the region are usually most active between November and February, and are a result of cold air picking up water vapor as it blows over warm lake waters. Generally, the heaviest amount of snow in Western New York falls near the southern end of Erie County, and lake effect snows typically diminish when Lake Erie freezes over.

In the winter season, warm air rises also off of Lake Ontario and is met with cooler air blowing from the southwest over the top of the Niagara Escarpment. This causes constant air movement as the warm air is forced back down the slopes towards the lake. Ontario has the smallest surface area of the Great Lakes, yet one of the deepest with max depth of 802’, which prevents it from freezing over. The overall result is over 205 frost free days of growing season on average. Less than 5% of winters reach temperatures below -10°. Winter vine kill and bud damage from early frosts are largely avoided. In the spring, the effect of the escarpment is reversed; the sun warms the land and the air rises to then settle over the lake.

Quick Facts

About the Niagara Escarpment Region

- Established October 11, 2005

- 8 Wineries

- 205 Day Growing Season

- 58 Farms, 1,067 Acres of Vineyard

- Native, Hybrids, Vitis Vinifera

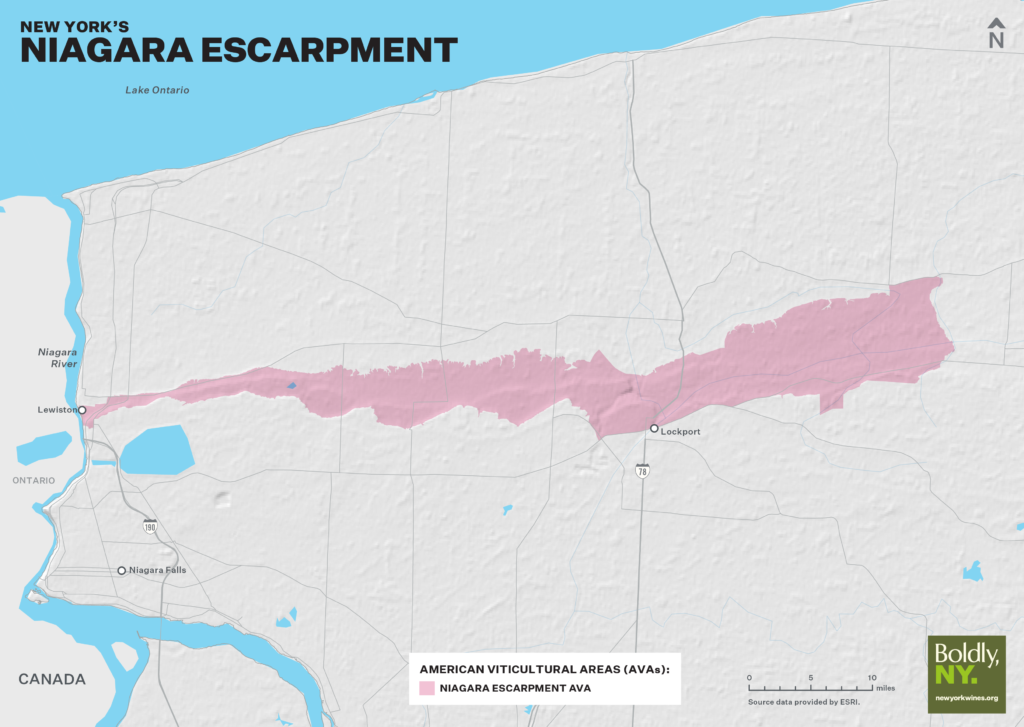

Region map

Explore More New York Wine Country: