“These are the rocks I collected on my recent visit to the Mosel!”

I’ve always liked rocks. As a child growing up on Long Island, I had a rock “garden” in the backyard, and trips to the mall were highlighted by a visit to the store Natural Wonders where I’d spend my pocket money on a new gem stone for my collection that was kept in a secret hiding spot in my bedroom. When Fluorite came home with me? Big day. I remember being a very self satisfied eleven year old for knowing the difference between igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary rocks before it was taught in science class. I like the thrill of the “hunt” for the right rock. Maybe I was just overly influenced by the adventures of Indiana Jones? Stones were my long lost artifacts. And to this day, I don’t like snakes or nazis.

Now, as an adult, and ultimately a wine professional I still collect two sets of rocks – one set lives in a jar, just stones from my travels that I’d pocket on visits to a new beach or on a hike. My wife, a self-proclaimed minimalist, doesn’t get it – but I look at the jar and know that each has a memory, specific or otherwise. I like that if it wasn’t for me, those rocks would have absolutely no business being together. A big world in a little jar.

The other set, those are from my visits to wine regions. I keep those organised in individual jars and baggies, sometimes labeled by region, sometimes a specific vineyard. Compared to the climate, weather, sun exposure, etc. – the rocks are tangible, you can hold them in your hand, a little bit of earth from this place that is the only place that could have made a wine that tastes like this. They have specific properties that you can see and feel. I do this because I am a believer in the concept of “terroir” – that wines, when well made, showcase a sense of place – and the rocks and soil are just one important piece of that bigger picture. My career pursuit of wine is similar, to be a student of wine is to be a student of the world, and wine touches on so many different disciplines – history, chemistry, anthropology, biology, etc. – I’m never bored, because I’ll never know it all. And so today, I’ll wear my geology hat.

With that said, I’m no scientist (I have a theatre degree), and admittedly my knowledge of geology doesn’t expand much beyond high school science class, so in the paragraphs that follow, I’ll do my best to explain the differences in the rocks and soil of New York State’s two major wine regions – Long Island, and the Finger Lakes, and with a look at a pair of single-vineyard wines from each place, we can dig in (pun intended) to why it matters.

For context, we should touch on this much-used term of ‘minerality’ – with many a wine writer and sommelier waxing poetic, “Oh, this wine reminds me of walking along a riverbank after the rainfall when the sun is drying the rain off the rocks…”

…what?

Here’s the thing — if you’ve never walked along a riverbank after the rainfall when the sun is drying the rain off the rocks — you’ll never smell that in a wine. The part of your brain that processes flavour is closely related to the parts of your brain that manage memory and emotion. Literally what makes you, you! And so there are no river rocks used in the production of the wine, but there are chemical and mineral compounds in the wine that remind our brains of something we’re familiar with. For our somm, it’s wet rocks after rainfall. For me, it may be writing on a chalkboard in school.

And so to build my palate vernacular and have the best understanding of minerality possible, I have licked every rock in that second collection of mine. Nothing gratuitous now (I can feel your judgement.) To best understand minerality, I try to liken it to the smells and tastes of everyday occurrences and items, such as: wet concrete, chalk dust in a classroom, dirt on my golf clubs, wet earth on my boots after a hike, flint – from a struck match perhaps, petrol at the gas station, tar, etc..

It’s worth noting that the correlation between the rocks/soil and the resulting wines produced from that land is not necessarily all about flavour. Just because a vine is planted in chalk soils, it does not necessarily mean the resulting wine will taste like chalk. The root system of a vine is not a highway for flavour from the ground to the fruit.

However, a recent study published by the Catena Institute claims to prove the presence of ‘Terroir’ through compound markers in an analysis of wines from single vineyard sites throughout Chile.

“For the first time, this study shows that the terroir effect can be chemically described from vintage to vintage in larger regions as well as in smaller parcelas (parcels). We were able to predict with 100% certainty the vintage of each wine of our study through chemical analysis.” – Dr. Laura Catena

But can a human perceive these markers, or are our brains making them up? Pascaline Lepeltier said it best in Alice Fiering’s “The Dirty Guide to Wine” –

“There’s no minerality in wine. One cannot taste the small oyster shells, Exogyra virgula, in a Chablis, or the taste of basalt in wines from Mount Etna. But yet, even if the scientists and the technical wine people tell us it isn’t so, that doesn’t mean that a sense of place doesn’t get delivered and that dirt and soil don’t have a part in it. Even if no one really yet understands “how” this can happen. Science is a work in progress trying to understand the “vital impetus”, within the limits of our mind.”

I think we’ll find that there’s a big impact on the viticultural practices, starting with what’s planted where – the soil creates specific conditions for the fruit, and a cascade of additional decisions will follow, a choose-your-own-adventure of winemaking, which ultimately affects the flavor.

The Long Island Region

Long Island stretches for 120 miles, parallel to the coast of Connecticut. It is both the longest and the largest island in the contiguous United States. It’s northern coast is separated from the mainland by the Long Island Sound. It’s southern border is the Atlantic Ocean. To the west it is separated from the Island of Manhattan and the Bronx by the East River. It is approximately 23 miles wide at its widest. The east end of the island splits into two forks, with the Peconic bay separating them. Long Island is home to Queens and Brooklyn, stacked on the west end, and extends into Nassau and Suffolk counties heading east. The further east you go, there is less development, more open spaces and agriculture. It is here when the overwhelming majority of vineyards and wineries are found. They are primarily on the North Fork of the island, which is offered the most protection from the ocean influence.

Formed by the advance and retreat of two ice sheets during the Cretaceous (Dinosaurs) and Pleistocene (no más dinosaurs / most recent ice age) that brought with them weakly consolidated to unconsolidated gravels, sands, and clays.

“The soils of our Mudd Vineyards were created approximately 10,000 years ago from sand, silt, clay and gravel sorted by melting glacial waters from the terminal moraine of the last Wisconsin Age glaciers.” – Larry Perrine, Partner, Channing Daughters

In its essence, Long Island is a really big sandbar just off of the shores of the mainland continental United States dropped there by glacial activity about 21,000 years ago! The north shore of the island is quite rocky, and the southern shores, unprotected from the Atlantic ocean, feature very fine sandy beaches.

I grew up on the north shore of Long Island, about 30 miles give or take from Long Island’s North Fork vineyards. The beaches on the shores of the Long Island sound were the playgrounds of my childhood, and the haunts of my teenage years. And while I didn’t explore the wineries until I returned to New York after university, when I consider the terroir of the region, I am flooded with the memories of these beaches, the shells, the stones (great for skipping), and the sand. That’s what I think about when I think about Long Island wines.

“The soils of the North Fork differ very little in the loam/sand/silt composition however the highest variable is the sand. This changes how quickly summer rains percolate through and out of the root zone.” – Russell Hearn, Winemaker, Suhru Wines.

The soils of the Long Island wine region are often likened to that of Bordeaux, which not only shares similar maritime influence, it also boasts high concentrations of gravel and sand. There, it’s alluvial in nature (sediment deposited by the rivers) whereas Long Island is glacial deposits. Bordeaux varieties, such as Merlot are widely planted on Long Island.

CHANNING DAUGHTERS Sauvignon Blanc – Mudd Vineyard

Speaking with Larry Perrine, Partner – I learned that the vineyard site is composed of two separate sites with unique soil types and landscape positions. It seems that even single vineyard wines can really be blends – the terroir can really be that specific that it warrants individual approaches.

“These soil materials were deposited in “outwash plains” creating the landscape of Long Island. Soils created on flatter outwash plains are quite high in silt and fine sands. Soils formed on hills have more sand and gravel and have lower water holding capacity, hence lesser vine growth.

“These soil materials were deposited in “outwash plains” creating the landscape of Long Island. Soils created on flatter outwash plains are quite high in silt and fine sands. Soils formed on hills have more sand and gravel and have lower water holding capacity, hence lesser vine growth.

The Haven Silt Loam soil of the Mudd Vineyard comprise half of the Sauvignon Blanc planting and are located on flatter terrain. The other half of the planting is found on a hilly site on Riverhead Fine Sandy Loam soil, with a significant percentage of gravel.

Both soils produce high quality Sauvignon Blanc with a different aroma profile. The heavier soils on Haven produce wines that lean toward the greener-tinged aromatics, while the drier, hilly Riverhead soils produce riper, more tropical aromas. These two sites are about 40 meters apart. So the meso-climate is the same while the soil characteristics play a definite role in creating a more complex wine when the fruit from both sites is processed together.”

The final wine is definitely a sum of its different parts. Stainless steel fermentation let’s the fruit shine – there’s nothing but grapes providing all that great texture. The nose is focused – clean citrus, just enough fresh herbs to say “I’m sauvignon blanc!” Riper fruit on the palate, very fresh stone fruit, tropical juiciness, finishing with a great exotic spice.

SUHRU WINES Single Vineyard Teroldego

Next I connected with Russell Hearn, Winemaker of Suhru WInes –

“The soils have excellent internal drainage, modest fertility, and moderate water-holding capacity which control and limit the impact of the periodic summer rains, controlling vine growth and promoting grape ripening in the fall. The vineyard our Teroldego is grown at is moderately high in the loam/silt content so retains water a little longer than others.

This site is a little elevated versus its surrounding land so it receives all the wind generated from the land/water effect of a Maritime Climate. This helps decrease humidity by enhancing air movement to reduce ‘fungal disease pressure’.

Our cool Maritime climate is very suitable to the ripening requirements of Teroldego. It is suited as it is an early ripening red (early to mid October) as it does not like/need a lot of heat for maturity.”

Here, it seems that we have the right combination of geological factors, soil, position, elevation to help maximise the positive influence of the climate! Teroldego is a rarity on Long Island, a lesser-known Northern Italian variety that has found a happy home in this unique vineyard.

The colour is striking, a deep purple. A mixed berry compote follows with great acidity, there’s green notes, blackberry leaf and bramble, and friendly tannins perfect for complementing foods.

The Finger Lakes Region

The eleven long, thin, “finger-like” lakes run parallel north to south in the northwest corner of New York State. It’s like a giant dragged their fingernails down the map. In reality, it was a glacier – also responsible for the great lakes to the north, the Hudson River and the rest of the topography of New York State to the south including, you guessed it, Long Island!

Moraines are the ridges of till or rock debris which piled up or were dumped along the edge of the ice. What was the effect of this glacial debris? The Valley Heads Moraine, a major moraine across central New York, closed the southern ends of several formerly south-flowing river valleys. The Finger Lakes were produced with the damming of these valleys.

In the middle of the region you’ll find Seneca Lake, the largest – 38mi long and 1mi at its widest point, and over 600ft deep! It’s so deep, it’s the only one of the lakes that doesn’t freeze over in winter – an amazing feat. It’s so deep that the United States Navy tests sonar equipment here. That depth has a profound effect on the conditions in the surrounding areas. The “lake effect” moderates the temperatures on the surrounding shores – it doesn’t get as cold in winter or as hot in summer. Unlocking the key for vitis vinifera production. And the winters get COLD! Frost and even trunk damage is a real concern.

A few hundred million years before the Ice Age, the area was a vast seabed. DEVONIAN shales, limestones, sandstones, and conglomerates define the soils of the region.

When I think of the Finger Lakes, I think of hiking the Watkins Glen Gorge Trail, with its terraced layered cliff sides carved over the years by water flowing from higher ground. I can hear the crunch of the fragile shale under my feet. I think about lunches on the shore of Seneca Lake, skipping the flat smooth stones across the water. That’s what I think about when I think about Finger Lakes wines.

Shale is essentially young slate, the latter formed by metamorphosis – time (millions of years) and pressure will get it there. Slate is the main rock type found in one of the world’s most famous Riesling wine regions – the Mosel Valley in Germany. Both boast very low percentages of permeability, meaning they don’t hold much water (slate practically none), and drain very well. Shale also has a high fissility – the ability or tendency of a rock to split along flat planes of weakness. Perfect for vine roots to wriggle through the cracks and spaces in search of water.

LAMOREAUX LANDING Riesling – Round Rock Vineyard

I had the pleasure of catching up with Josh Wig, Winemaker at Lamoreaux Landing, on the east side of Seneca Lake…

When asked what is special or unique about the Round Rock Vineyard in terms of its geology, Josh said,

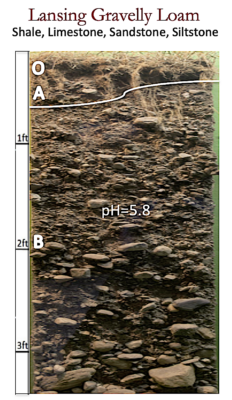

“While our estate consists entirely of calcareous glacial till, this 16-acre vineyard is our only Riesling vineyard planted in Lansing Gravelly Silt Loam soil, a medium textured stratified soil comprised largely of shale, limestone, sandstone, and siltstone. Elevation ranges from 850 to 1000 feet along a very steep western-facing slope that starts about 2/3 of a mile above Seneca Lake.”

“While our estate consists entirely of calcareous glacial till, this 16-acre vineyard is our only Riesling vineyard planted in Lansing Gravelly Silt Loam soil, a medium textured stratified soil comprised largely of shale, limestone, sandstone, and siltstone. Elevation ranges from 850 to 1000 feet along a very steep western-facing slope that starts about 2/3 of a mile above Seneca Lake.”

It’s interesting to note that “good” soil is not always “good” soil! It can affect decisions like how to train and work the vines in response to the soils characteristics. –

“The rich loam is well-drained and loaded with natural minerals, nutrients, and organic matter, allowing the vines to set deep roots and thrive under our cool-climate conditions. Our biggest challenge is slowing them down, as the soils are so vigorous. We do this by using a vertically split trellis system called Scott Henry, which devigorates the lower fruiting wire by training it toward the ground.”

Limestone-based soils are prized for vineyards, and Josh noted the common thread linking some of the finest growing regions around the world.

“Limestone decays to Calcium Carbonate, which naturally balances the soil’s pH and results in lots of free Calcium available to the vines. Calcium, while being one of, if not the most important macronutrient for the vines, also assists in the uptake and regulation of most of the other essential macro and micronutrients. Calcium accumulates in the skins to fend off disease pressure and allows the grapes to retain acidity late into the season. The result is happy vines that produce balanced fruit resulting in wines with mouthwatering acidity, complex phenolics, pronounced minerality, and true expression of place.”

And he’s not wrong! The aromatics leap from the glass – grapefruit pith and white flowers, underpinned by a cool minerality – the sensation akin to a cool stone countertop on a warm day. The wine bursts onto your palate with riper fruit, balanced sweetness and a lively acid underpinning that zings forward long after you drink it.

DAMIANI WINE CELLARS Lemberger, Sunrise Hill Vineyards

Last but not least I chatted with Glenn Allen, Owner of Damiani Wine Cellars:

It’s hard to explore the Finger Lakes and imagine the place without its vineyards. They seem very elemental. But we’d be remiss without acknowledging the people that select and care for these sites!

“We have a special relationship with “Sunrise Hill”. Owned and farmed by Bob and Kathy Ruis, Sunrise Hill vineyard is a beautiful pastoral setting overlooking the lake on a gentle slope that catches the morning sunrise. While the soil, sunshine, slope and overall microclimate are hallmarks of great terroir, the quality of fruit is a testament to the diligent and passionate work of Bob and Kathy. They learned how to grow grapes from DWC co-owner/grower Phil Davis and from the beginning have been a sister vineyard to DWC. Coming from this close relationship are high quality grape varietals so uniquely expressive that DWC has bottled them as a single vineyard expression, including Gewurztraminer, Pinot Noir, and of course the King of Sunrise Hill (as Kathy calls it), Lemberger.”

…Why Lemberger? What factors go into deciding what wines get a single vineyard designation?

“Lemberger thrives at this site, year after year producing a wine with lush fruit, exotic flavors, and unique almost perfumed aromatics. DWC sources Lemberger from other high-quality sites, but none have such intensity and expression. Sunrise Hill Lemberger is one of the few wines DWC bottles as a single vineyard EVERY vintage because it is so consistent, so good, so unique. Only the best barrels are chosen for single vineyard or reserve designation, and only make the cut in certain years when the winemaker and owners agree it would be criminal to blend away such a unique and fantastic cuvee. Production is limited to about 175 cases.”

With such a close relationship to the site, and consistent results delivered each vintage, it’s not a difficult decision to highlight the place with a single vineyard bottling. Well deserved.

“By properly farming on a great site like this, one can achieve great aromatics, concentration, and depth across the palate. In young vines, much of the plant physiology takes place above ground and in the first few feet of soil depth that make up its active microbiome. As the vine matures, it sends roots down into the deep layers where it finds pockets of different minerals and extracts from them additional unique qualities that set it apart from young vines and which are truly expressive of site. The unique combination of geologic attributes, with passionate farming and winemaking, allows Sunrise Hill to express flavors, aromatics, and mouth-feel that are as unique as they are beautiful.”

It’s interesting to consider that a site’s true potential might not show itself until the roots get deep enough to unlock it!

Lemberger is a late-ripening red-skinned variety. The grape was documented in Austria in the second half of the 18th century and is cultivated there to this day (as Blaufränkisch) in Burgenland and near Vienna. In Hungary it is known as Kékfrankos. It is showing excellent potential in the cool climate finger lakes, site specificity is important, as you need the lake effect to extend the season long enough to ripen.

This wine is joyously-fruited. Black and blue berries mingling with judicious oak and spice, medium-bodied, with thoughtful rusticity.

In closing – New York Rocks! The complex geologic history of these wine regions is only a small piece of the puzzle that comes together to create world-class terroir in New York State. The best wines come from humans that understand the terroir “mosaic” and make smart decisions to harness and showcase this potential.